Key Highlights

- Globally, food items are costing significantly more than they did last year

- Agriculture prices hit by a perfect storm of war, global warming and supply chain issues

- Potential for more pain as consumer price rises yet to mirror those borne by food producers

Drought and war

From Singapore to the US, and from a slice of bread to a four-course meal, consumers are starting to feel to effects of higher food prices. While this has been largely blamed on the Russia–Ukraine war, even before its outbreak, food price inflation was already at a decade-high.

South America, one of the world’s most important regions for agricultural production, is seeing its second consecutive year of drought. In particular, Brazil and Argentina, two of the world’s largest producers of corn, soybeans and sugar, have had smaller harvests this year. Coupled with Covid re-opening demand, these inventories are now unusually tight

Now, with a war raging on Europe’s doorstep, the food stress has only widened and deepened. While India and China are the world’s biggest producers of wheat, much of this is retained for domestic consumption. This puts Russia in first place within the ranking of top wheat exporters, and Ukraine is fifth. Together, according to the International Trade Centre, in 2020 they accounted for 26 percent of the world’s wheat exports, and 24 percentage of its barley exports. They also made up almost half of global exports of sunflower, safflower and cotton seed oil.

Looming hunger crisis

The drying up of Russian wheat exports is hitting some countries particularly hard. According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), there are some 50 countries that rely on Russia and Ukraine for 30 percent or more of their wheat imports.

This includes several developing countries in North Africa, with Egypt and Turkey accounting for nearly half of Russia’s annual exports. Bangladesh and Pakistan are also major importers of Russian wheat. In addition, another group of food-producing countries in Europe and Central Asia are heavily dependent on Russian fertilizers, without which their output would be much diminished.

While sanctions are a factor in the supply bottleneck, the FAO notes that the closure of Black Sea ports and Ukraine’s internal rail systems are the bigger problem. Meanwhile, some countries have reduced their import tariffs or enforced export embargoes of their locally produced wheat, as India did recently. This has only exacerbated the dire predicament that the most vulnerable importers now find themselves in.

Basic necessities

However, the problem is not confined to these countries. The wheat shortage and strong demand has caused global prices to more than double, from an average of US$500/bushel in 2021 to US$1200/bushel this year. Rapeseed oil and sunflower oil prices have risen more than 60 percent.

Aside from these two food commodities, dairy, meat and sugar prices have also been trending up. Dairy prices rose by 23.5 percent in April compared to a year ago, driven by lower output in Europe and higher demand for butter as a substitute for sunflower oil and margarine. Meanwhile, meat prices reached new highs in 2022, although lockdowns in China allowed prices to moderate marginally. Brazil’s poor sugar cane harvests are propping up sugar prices.

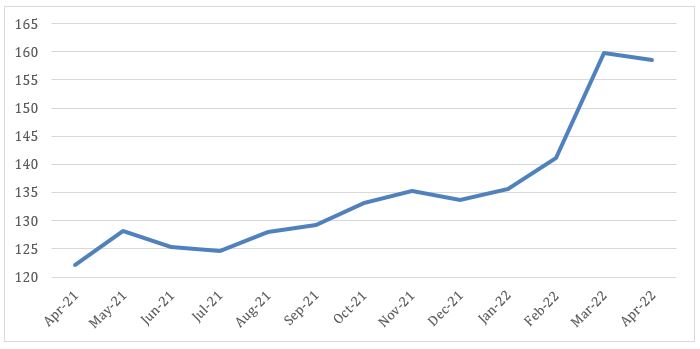

Not surprisingly then, the FAO’s Food Price Index, which tracks a basket of all five food categories, reached an all-time high in March this year, but managed to dip slightly in April. The World Bank’s announcement last week that it will make US$30 billion available for a range of agriculture, water and irrigation, and nutrition-related projects has helped prices to stabilise somewhat, but is unlikely to result in a major price adjustment.

Figure 1: FAO Food Price Index

Source: FAO

US food inflation

In the US, the higher price of these basic foodstuffs is flowing through into packaged food products. As a result, average US grocery bills are rising at a faster rate than most families would remember. In April, while the overall Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose by 8.3 percent year-on-year, food prices rose faster at 10.8 percent. This is the highest food inflation seen in over four decades.

Much of this increase is the result, not of higher wheat prices, but of the 14.3 percent rise in the cost of meat, poultry, fish and eggs. Fruit and vegetable prices rose by less but a still-substantial 7.8 percent. One of the primary drivers of US food inflation is the 50 percent rise in the cost of agricultural chemicals needed for fertilizers and pesticides such as nitrogen, potassium and phosphorous. Russia is currently the world’s largest exporter of fertilizers. The US Meat Institute has also highlighted the shortage of agricultural workers, food packers and port workers as “the immediate challenge to (the US’s) food supply chain”.

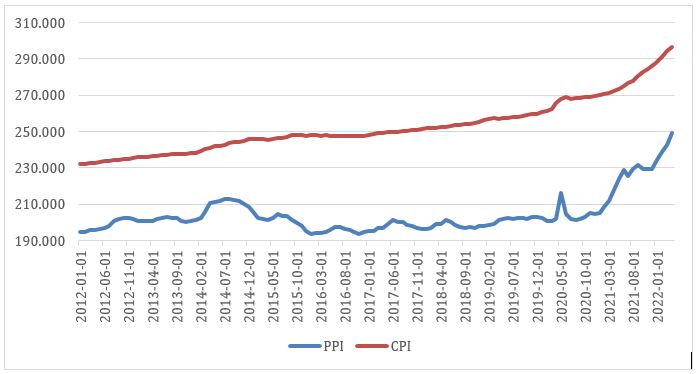

Furthermore, not all these costs have been passed on to the consumer. Some economists note that this has started to occur, leading US food companies’ previously tight profit margins to show good improvement. However, it would appear that producers and retailers are still wary about raising their prices too quickly. As a result, consumer price rises since 2021 have not yet caught up to producer price rallies, but given that demand remains strong, this can be expected over the course of the year.

Figure 2: US PPI vs CPI

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED). PPI is the Producer Price Index by Industry: Food Manufacturing, Index Dec 1984=100, CPI is the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Food and Beverages in U.S. City Average, Index 1982-1984=100

Asia food inflation

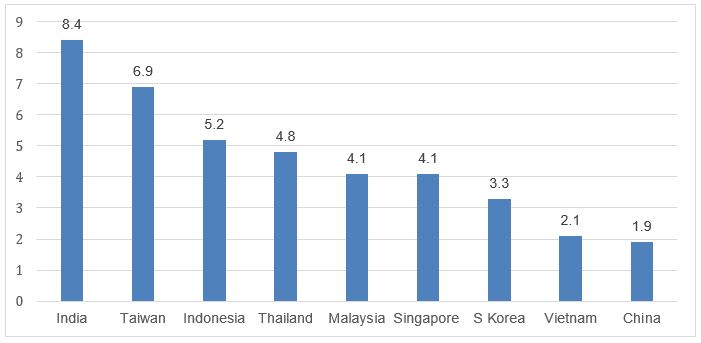

Figure 3: Food Inflation in Asian countries, April 2022

Source: Trading Economics

Over in Asia, the food inflation picture appears more tame, for now. However, there are signs that Asian economies’ resilience to higher global prices is coming to an end. For example, April’s inflation numbers from China to India to Thailand, while still relatively low, were higher than forecast.

As a result, markets are already pricing in higher inflation expectations and more aggressive central bank tightening. A good example is Korea, where government bond yields have jumped in the past week, amid comments from Bank of Korea Governor Rhee Chang-yong that bigger-than-usual interest rate hikes are possible in the coming months in order to control inflation.

It also appears that the process of passing on higher prices to Asian consumers has not started in earnest. There are fears therefore that inflationary pressures may get worse before getting better. The Monetary Authority of Singapore’s April CPI report warns that this pass-through process is set to intensify, resulting in “core inflation significantly above its historical average through the year.”

Inflation hedges

Given the many variables behind food inflation, food prices tend to be more volatile and unpredictable than other forms of inflation. Yet it is a well-known fact – captured by Engel’s Law – that the percentage of income allocated to food rises as incomes fall. This can be seen by comparing the share of consumer expenditure on food across countries. In developed nations such as the US and UK, this ranges from 8 - 10 percent, whereas in China and Malaysia, this is closer to 20 percent, and in Pakistan. the figure rises to 40 percent

There is therefore good reason for Asian investors to attempt to hedge against rising food prices. This can be via investment opportunities within the food and agricultural sector, for example, fertilizer producers, food manufacturers, palm oil plantations and farm equipment companies.

Furthermore, while interest rates are expected to rise in the coming period, this is unlikely to keep pace with food price hikes. Individuals may therefore want to ensure that they are receiving regular investment income, whether through equities, higher-yielding bonds or REITs, to counter the impact of elevated monthly grocery and restaurant bills.

This publication shall not be copied or disseminated, or relied upon by any person for whatever purpose. The information herein is given on a general basis without obligation and is strictly for information only. This publication is not an offer, solicitation, recommendation or advice to buy or sell any investment product, including any collective investment schemes or shares of companies mentioned within. Although every reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy and objectivity of the information contained in this publication, UOB Asset Management Ltd (“UOBAM”) and its employees shall not be held liable for any error, inaccuracy and/or omission, howsoever caused, or for any decision or action taken based on views expressed or information in this publication. The information contained in this publication, including any data, projections and underlying assumptions are based upon certain assumptions, management forecasts and analysis of information available and reflects prevailing conditions and our views as of the date of this publication, all of which are subject to change at any time without notice. Please note that the graphs, charts, formulae or other devices set out or referred to in this document cannot, in and of itself, be used to determine and will not assist any person in deciding which investment product to buy or sell, or when to buy or sell an investment product. UOBAM does not warrant the accuracy, adequacy, timeliness or completeness of the information herein for any particular purpose, and expressly disclaims liability for any error, inaccuracy or omission. Any opinion, projection and other forward-looking statement regarding future events or performance of, including but not limited to, countries, markets or companies is not necessarily indicative of, and may differ from actual events or results. Nothing in this publication constitutes accounting, legal, regulatory, tax or other advice. The information herein has no regard to the specific objectives, financial situation and particular needs of any specific person. You may wish to seek advice from a professional or an independent financial adviser about the issues discussed herein or before investing in any investment or insurance product. Should you choose not to seek such advice, you should consider carefully whether the investment or insurance product in question is suitable for you.