Key Highlights

- COP 26 starting this week once again puts China in the spotlight

- China’s decarbonisation efforts have taken a backseat amid recent power shortages

- The fine balance between green and developmental goals will define China’s economy going forward

Do or die

The United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 26) opened this week with arguably the most sobering set of climate change statistics and climate action demands that global leaders have ever faced. This “no more excuses” conference is seeking to enhance countries’ carbon emission targets in an attempt to meet a 1.5C (or at least the “well below 2.0C”) global warming limit.

Back in 2015, 196 countries adopted the Paris Agreement to collectively achieve this limit. Each country is responsible for setting its own emission-reduction targets called NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions). The Agreement works on a five-year cycle and calls on countries to ambitiously increase their climate action with each renewed NDC submission.

Postponed to 2021 due to the Covid pandemic, UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres addressed the first day of COP 26 with a plea for countries to avert a climate disaster. “Recent carbon announcements might give the impression that we are on track to turn things around,” he says. “This is an illusion.”

All eyes on China

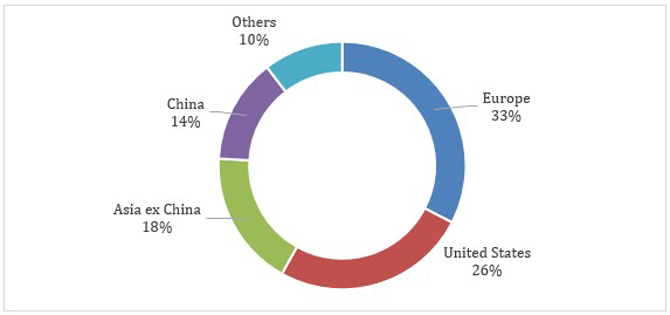

Along with US and Europe, China is the subject of much interest at COP 26. It has been the world’s biggest carbon emitter since 2008, although this requires some qualification. On a per capita basis, China is ranked 48th, while on a historical basis - from 1750 to 2019 - its share of total carbon emissions was 13.7 percent, only about half that of the US and Europe.

That said, China was responsible for well over a quarter of global carbon emissions in 2019. Its strong commitment is therefore needed not only to meet global limits, but to show the way for other developing nations.

Figure 1: Share of Total CO2 Emissions 1750 - 2019

Source: Our World In Data/ UOBAM

Not surprisingly then, the lack of new pledges in the updated NDCs released by China on the eve of COP 26 was met with some disappointment. However the NDC provided more detailed plans for fulfilling President Xi Jinping’s promise of carbon neutrality by 2060. There were also a few goal upgrades. Non-fossil fuels that comprised just 16 percent of China’s total energy mix last year is targeted to reach 25 percent (up from 20 percent) of China’s total energy consumption by 2030 and 80 percent by 2060.

Unintended consequences

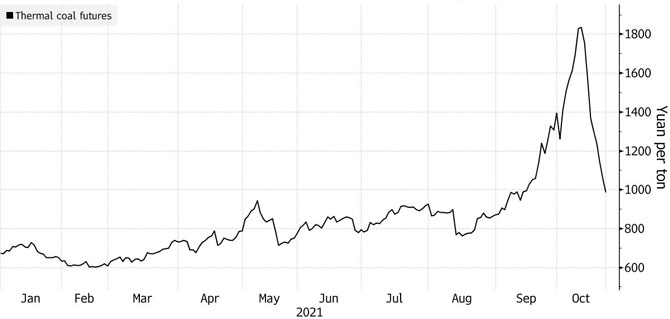

Nevertheless the NDC noted that any short term shift away from coal was unlikely. Given the country’s energy demand, urbanisation and industrialisation trends, the report acknowledged that its coal dependency would not be easy to eradicate. And indeed, there can be no clearer demonstration of this than in the week preceding COP 26, when the authorities stepped in cool the coal market in the face of slowing industrial production.

Over the previous few months, regulatory measures to address coalmine safety and environmental concerns had caused China’s coal production to stall. In the meantime, post-Covid demand for coal has grown 12 percent year-to-date. This supply-demand imbalance has resulted in China’s worst energy crunch in years. Not only are coal prices at levels not seen since 2015, power shortages have caused manufacturing activity to decline. China’s Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) for October fell to 49.2 from an already weak 49.6 in September.

As with policy clampdowns in the property sector, attempts to introduce environmental and social measures in the energy sector has had both intentional and unintended consequences. While somewhat higher coal prices may have expected, the scale of the rise has led to electricity-generating companies operating at a loss. Their unwillingness to replenish inventories led to power outages in many major provinces, including Guangdong, Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning. This in turn has particularly affected energy-intensive industries, at a time when manufacturing accounts for over 40 percent of China’s GDP, up from around 35 percent five years ago.

The supply chain tightrope

The Chinese authorities’ price cap on coal will bring it down from a previously anticipated range of RMB800 - 1,000 to RMB600 - 800. As a result of this intervention, Chinese coal futures have fallen 47 percent since hitting a record high in mid-October.

Figure 2: Thermal Coal Futures Jan – Oct 2021

Source: Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange

Meanwhile, in contrast to previous production controls, coal mining companies have been told to increase output. Just in the last week, the National Mine Safety Administration approved production increases at another 153 mines, on top of those given to mines in Yunnan, Shanxi and Inner Mongolia. At least 100 million tonnes more coal is being made available this quarter to cope with winter conditions.

In doing so, the authorities acknowledge that this conflicts with the country’s decarbonisation goals. However, in a set of guiding principles, they suggest that there is a need to balance between carbon emission and developmental goals, and between the short and long term. The message is clear: containing supply chain risks must take precedence over decarbonisation efforts, at least in the short term.

The divide between green and economic targets will dissolve over the longer term as climate changes takes a sustained toll on the economy. In the short term however, and as we are witnessing in real time today, China will likely resort to a series of start and stop measures in its attempt to decarbonise.

In line with UOBAM’s sustainability focus, we foresee higher risks and lower earnings potential within the coal mining sector. Given that coal prices have been the primary driver for revenue growth, even intermittent price constraints could have a prolonged negative impact. On the other hand, we believe a medium term stabilisation of coal prices will allow the utilities sector to increase its inventories and operate profitably, helped by the introduction of electricity tariffs. Valuations within the utilities sector also appear relatively cheap based on forward Price-to-Book (P/B) ratios. However, we would actively seek power producers that are looking to diversify away from coal to other energy sources.

This publication shall not be copied or disseminated, or relied upon by any person for whatever purpose. The information herein is given on a general basis without obligation and is strictly for information only. This publication is not an offer, solicitation, recommendation or advice to buy or sell any investment product, including any collective investment schemes or shares of companies mentioned within. Although every reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy and objectivity of the information contained in this publication, UOB Asset Management Ltd (“UOBAM”) and its employees shall not be held liable for any error, inaccuracy and/or omission, howsoever caused, or for any decision or action taken based on views expressed or information in this publication. The information contained in this publication, including any data, projections and underlying assumptions are based upon certain assumptions, management forecasts and analysis of information available and reflects prevailing conditions and our views as of the date of this publication, all of which are subject to change at any time without notice. Please note that the graphs, charts, formulae or other devices set out or referred to in this document cannot, in and of itself, be used to determine and will not assist any person in deciding which investment product to buy or sell, or when to buy or sell an investment product. UOBAM does not warrant the accuracy, adequacy, timeliness or completeness of the information herein for any particular purpose, and expressly disclaims liability for any error, inaccuracy or omission. Any opinion, projection and other forward-looking statement regarding future events or performance of, including but not limited to, countries, markets or companies is not necessarily indicative of, and may differ from actual events or results. Nothing in this publication constitutes accounting, legal, regulatory, tax or other advice. The information herein has no regard to the specific objectives, financial situation and particular needs of any specific person. You may wish to seek advice from a professional or an independent financial adviser about the issues discussed herein or before investing in any investment or insurance product. Should you choose not to seek such advice, you should consider carefully whether the investment or insurance product in question is suitable for you.