Climate Pledges Could Transform ASEAN Agriculture

In Part 2 of our series on COP26 outcomes, we look at how the region can protect its food security, and the opportunities for agritech and foodtech companies

Big strides for ASEAN

One of the most significant COP26 outcomes for ASEAN countries is the promise to reduce deforestation and methane emissions.

The Declaration on Forests and Land Use, endorsed by 141 countries, including Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam and Singapore, is deemed “pivotal” as it covers 91 percent of existing forests. It commits signatories to “working collectively to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030 while delivering sustainable development and promoting an inclusive rural transformation.”

Equally important is the Global Methane Pledge to reduce methane emissions. Initiated at the COP26 summit, the pledge was made by 105 participants, including ASEAN countries such as Indonesia and Vietnam. Methane is a greenhouse gas with a potency for global warming that is 30 times higher than carbon dioxide (CO2). Participants signed up to collectively reduce global methane emissions at least 30 percent from 2020 levels by 2030, on top of their existing CO2 emission pledges.

Impact on agriculture

Both pledges have profound implications for agriculture in the region. It is estimated that 80 percent of forest has been lost to agriculture. Within Southeast Asia, while legal and illegal logging is a major problem, the majority of forested land is in fact cleared for growing commodity crops such as palm oil, soy, cocoa, and coffee. Malaysia and Indonesia, where deforestation is most severe, currently account for 90 percent of the global palm oil market.

Agriculture is also the largest source of anthropogenic (i.e. human-influenced) methane, and is responsible for about a quarter of global emissions. Within agriculture, the raising of livestock is the primary activity leading to methane emissions. It also occupies the majority – 77 percent – of agricultural land and yet is only 17 percent of the food consumed globally.

Rice cultivation by using paddies (flooded fields) is another significant source of methane emissions. This widely practiced method of rice growing allows methane-emitting bacteria to build up, and is estimated to result in emissions equivalent to international aviation.

This suggests that, in order to maintain their cash crops and food output, these countries will need to accomplish vastly higher productivity. Additionally, agriculture in this region must cope with population growth and an expanding middle class. ASEAN’s population is expected to grow at an average rate of one percent per annum over the next decade.

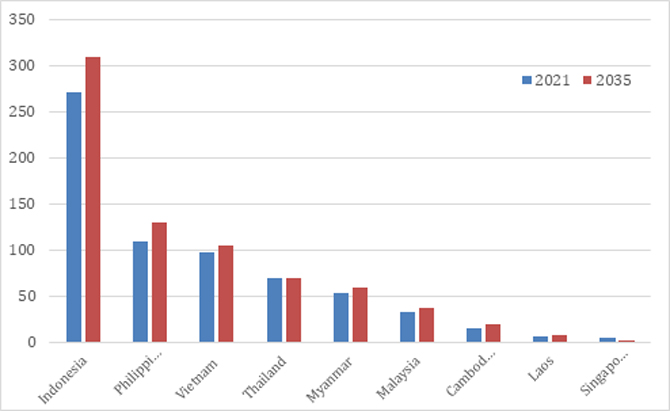

Figure 1: Population forecasts for the ASEAN region (in millions)

Source: Statista/ UOBAM

Smart agriculture to the rescue

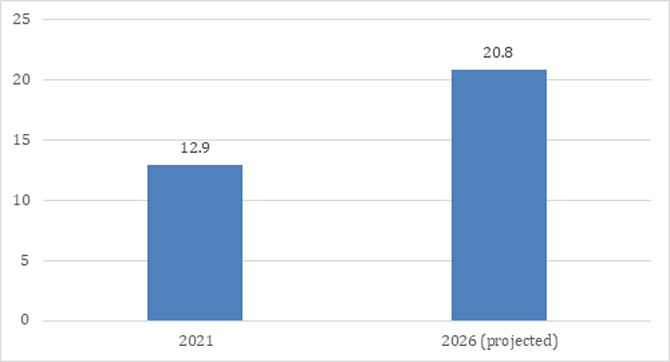

Over the past few years, an agritech and foodtech market has emerged to take on this productivity challenge. Vendors include those offering automated farm equipment, climate resistant plant varieties, food supply chain optimisation, meat substitutes and vertical farming support. According to MarketsAndMarkets, the global smart agriculture market is forecast to grow at an annual rate of 10.1 percent to reach US$ 20.8 billion by 2026.

Within this, APAC is expected to grow the fastest during the forecast period, especially those in emerging countries such as India, China, and those in Southeast Asia. This growth will be driven by the increasing adoption of AI-driven variable rate technology (the ability to vary fertilisers and other inputs based on the soil or crop), smart irrigation and farming automation.

Figure 2: Smart Agriculture Market (in US$ billion)

Source: MarketsAndMarkets/ UOBAM

In the wake of COP26, this smart agriculture market could be spurred on to greater heights, with mature agritech companies in the US, Europe, India, and China the likely beneficiaries. Bilateral arrangements have also seen some large foreign companies, including several from Israel, finding their way into farming communities in Thailand and Vietnam.

These companies are offering less energy dependent and more water efficient ways of farming, innovations that even appeal to countries with limited land mass like Singapore. The city state’s goal to produce 30 percent of its nutritional needs by 2030 has caused agritech to become a new area of focus. Last year, Singapore government-owned investment company, Temasek, paid US$365 million to acquire a majority stake in Rivulus, an Israel-based irrigation solutions provider.

The rise of plant-based products

Another area of significant investment by the Singapore government is in food technology and especially plant-based meat production. Plant-based meat production emits 30-90 percent less greenhouse gas, and requires 47-99 percent less land as well as less resources than animal husbandry. Such environmental and climate-friendly solutions are all the more important as meat and seafood consumption in Asia are projected to grow by 78 percent between 2017 and 2050, according to a report by consultancy firm Asia Research and Engagement.

Given Asian consumers’ familiarity with soy-based foods, the plant-based meat sector is fast gaining ground in Asia. Zion Market Research estimates that Asia Pacific will have the biggest share of the global plant-based market, which is forecast to reach US$21.2 billion by 2025.

To capture this demand and satisfy its own food needs, Singapore is carving out a position for itself among plant-based producers. In 2020, the Singapore regulator became the first in the world to approve lab-grown meat for local consumption. Eat Just, a US-based producer of plant-based protein, is building a production facility in Singapore, as are Swiss multi-national food tech companies, Bühler and Givaudan.

Meanwhile, locally-based producers are taking hold in Thailand and Malaysia, where plant-based meat products are widely available at half the price of foreign brands. Let’s Plant Meat, Meat Avatar and More Meat are all popular Thai brands with regional ambitions.

Breaking the cycle

Agriculture and climate change are interwoven in ways that make it hard to disentangle. On the one hand, agricultural land use is a leading emitter of greenhouse gases, and some experts warn that its contribution may eventually surpass even that of fossil fuels.

On the other hand, extreme climate conditions look set to threaten agricultural production and profitability. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s special report on Climate Change and Land predicts that the stability of global food supply will decrease and disruptions to food chains will increase alongside the growing magnitude and frequency of extreme weather events.

Climate-conscious agritech and foodtech providers have the potential to break this vicious cycle. Collaborations between the private and public sector, such as the Global Alliance for Climate-Smart Agriculture (GACSA) have been formed to democratise advances in agritech. Food technology vendors are also gearing up to meet ASEAN’s nutritional needs. Over the next few years, the imposition of more climate-friendly limits on land use and agricultural practices can be expected to propel these sectors to the forefront of ASEAN economies.

This publication shall not be copied or disseminated, or relied upon by any person for whatever purpose. The information herein is given on a general basis without obligation and is strictly for information only. This publication is not an offer, solicitation, recommendation or advice to buy or sell any investment product, including any collective investment schemes or shares of companies mentioned within. Although every reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy and objectivity of the information contained in this publication, UOB Asset Management Ltd (“UOBAM”) and its employees shall not be held liable for any error, inaccuracy and/or omission, howsoever caused, or for any decision or action taken based on views expressed or information in this publication. The information contained in this publication, including any data, projections and underlying assumptions are based upon certain assumptions, management forecasts and analysis of information available and reflects prevailing conditions and our views as of the date of this publication, all of which are subject to change at any time without notice. Please note that the graphs, charts, formulae or other devices set out or referred to in this document cannot, in and of itself, be used to determine and will not assist any person in deciding which investment product to buy or sell, or when to buy or sell an investment product. UOBAM does not warrant the accuracy, adequacy, timeliness or completeness of the information herein for any particular purpose, and expressly disclaims liability for any error, inaccuracy or omission. Any opinion, projection and other forward-looking statement regarding future events or performance of, including but not limited to, countries, markets or companies is not necessarily indicative of, and may differ from actual events or results. Nothing in this publication constitutes accounting, legal, regulatory, tax or other advice. The information herein has no regard to the specific objectives, financial situation and particular needs of any specific person. You may wish to seek advice from a professional or an independent financial adviser about the issues discussed herein or before investing in any investment or insurance product. Should you choose not to seek such advice, you should consider carefully whether the investment or insurance product in question is suitable for you.